Division of Mammals

open weekdays 8am - 5pm

visitors welcome by appointment

information for visitors

phone: (505) 277-1360

fax: (505) 277-1351

museum administrator

open weekdays 8am - 5pm

visitors welcome by appointment

information for visitors

phone: (505) 277-1360

fax: (505) 277-1351

museum administrator

| In 1915, the U.S. government and private land owners began a coordinated trapping and poisoning effort against Mexican gray wolves (Canis lupus baileyi) as a policy to prevent them from “disrupting” the cattle and livestock industries. Wolf populations suffered severe declines and they became very scarce due to this deliberate extermination, as well as habitat loss (Ballantyne, 2022). By the 1930s, they were almost completely absent from the western United States. Wolves that were entering from Mexico were killed quickly. In 1950, U. S. Fish and Wildlife started sending staff to Mexico to set up a wolf-poisoning program, which they deemed a form of foreign aid (Biologicaldiversity.org). |

| The U.S. passed the Endangered Species Act in 1973, and these wolves were listed as endangered in 1976. By then, none existed in the U.S. Five individuals were trapped in Mexico between 1977 and 1980, referred to as the McBride lineage after the trapper who captured them. Three of those were taken by Fish and Wildlife to begin a captive breeding program. Four more that were already in captivity in Aragon and Ghost Ranch later proved to be pure-blooded and were added to the breeding program. These seven wolves are the “founders,” meaning that all Mexican gray wolves alive today are descendants of those individuals (Southwestwildlife.org). |

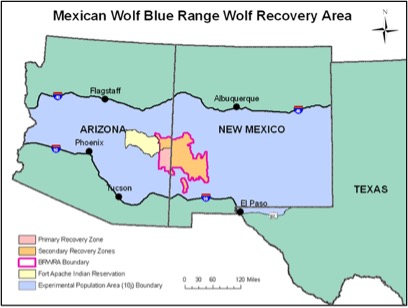

| In 1982, the Mexican Gray Wolf Recovery Plan was approved. The plan involved ensuring the wolves’ survival through captive breeding programs flowed by efforts to reintroduce the subspecies back into their historic range. The first phase of the plan did not include the goal of actually removing the wolves from the Endangered Species List, it consisted more of the temporary objective of beginning to reintroduce them into the wild (Ballantyne, 2022). Reintroduction began in 1998, where the first wolves were released into the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area in Southeast Arizona and Southwest New Mexico. In 2011, another release area was designated in Sonora, Mexico (Biologicaldiversity.org). By 2017, the first phase of the recovery plan was finished, and the new goal involved recovering the population to pre-endangered numbers and survivability. The two populations were to be redistributed all across their historic habitats (Ballantyne, 2022). As of December 2020, there were some 186 wild wolves in the U.S. (Southwestwildlife.org) and another 30 in Sonora and Durango, Mexico (Biologicaldiversity.org). |  The Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area seen on a map. It spans across central and southern Arizona and New Mexico, and a small section of Texas. The Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area seen on a map. It spans across central and southern Arizona and New Mexico, and a small section of Texas. |

|

Preserved historical specimens provide necessary temporal baseline information for understanding the ecology and spatial requirements of organisms, as well as tracking potential changes in species distributions over time. The historical range of the MSB wolf specimens show that this subspecies spanned across at least southwest New Mexico and southeast Arizona in the US. That distribution largely corresponds to the designated Blue Range Recovery Area. Historic ranges like these can be pooled from records from multiple museums to help determine core areas where captive-bred animal populations should be reintroduced although environmental conditions are changing rapidly on our planet. Unfortunately, relatively few Mexican gray wolves were historically archived in museums, meaning that available data on their natural history, taxonomic relationships, distribution, and fundamental biology remains limited. Today we collect many kinds of data on each specimen to ensure we gain as much information as possible (Galbreath et al., 2019) and that we are able to provide critical material to future studies. MSB collaborates closely with the US Fish and Wildlife Service to ensure that animals found dead in the wild are preserved, with tissue samples taken from multiple organs, gonads preserved, traditional museum preparations, and all locality data recorded. Measurements, reproductive data, and all parasites are carefully recorded and preserved. Museums provide detailed data and samples for research and management initiatives as we gain fundamental insights into organisms’ pasts, presents, and futures. |

A pie chart showing the distribution of Mexican gray wolf preserved specimens in different collections across the U.S. The MSB collection makes up an overwhelming percentage of the total. |

Mexican gray wolf. (n.d.). Biologicaldiversity.org.

Galbreath, K. E., E. P. Hoberg, J. A. Cook, B. Armién, K. C. Bell, M. L. Campbell, J. L. Dunnum, A. T. Dursahinhan, R. P. Eckerlin, S. L. Gardner, S. E. Greiman, H. Henttonen, F. A. Jiménez, A. V. A. Koehler, B. Nyamsuren, V. V. Tkach, F. Torres-Pérez, A. Tsvetkova, A. G. Hope. 2019. Building an integrated infrastructure for exploring biodiversity: field collections and archives of mammals and parasites. Journal of Mammalogy 100: 382-393.

Robinson, M. 2005. Predatory Bureaucracy: The Extermination of Wolves and the Transformation of the West. University of Colorado Press.